Comparing Europe To the USA

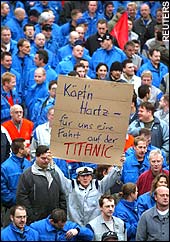

Research Notes American/Euro Culture Clash (Commonly Held Views) Why does the fact that Germans don't have to work so hard to have a good life make you so angry? Have you even been to Germany? Do you even have a passport? A good life? 12.6% unemployment rate, 40% of the population not working fulltime, working an average of 13% of their lifetime, and a per capita GDP that is two-thirds of the US? Yes, some inherit wealth, but most work hard for it. I work hard to provied myself with the lifestle that I have. My parents are both alive, and I probably won't get anything from them until I am old. The life expectancy on my Mom's side of the family is the late 80s. I am sorry that you don't own a home, but don't take it out on me. There are few things that irritate me more than people who say, "you own your own business? Wow! Must be nice to work 20-30 hours a week and rake in all that dough." I busted my ass (and still do so) to get where I am and took a financial risk to do so. That is why I resent some of these govt workers who work 37.5 hours a week, get tons of benefits (from my tax dollars), and didn't have to put up a nickel to do so. I know 2 ladies that work at the Liquor Board store (govt-controlled) who get $25 per hour to stock the shelves and run the till. Wow. How many years of university did they take for that? I know a lady who works for the Canadian govt who brags about taking 30-40 minute coffee breaks (with her supervisor) and takes a hour and a half for lunch (instead of an hour). That is about 70 minutes per day of production per day that she wastes and I am not even counting everyone else in her dept. Does that sound efficient to you? It is MY tax dollars that are paying for that inefficiency. Although I make more money than her...On a per hour basis, she probably does better than me...and I am helping to pay for that waste. Also, I am a dual citizen. I was proud to vote for The Mighty Dubya last year. You just don't get it. Germany's economy is in the toilet; their govt is trying to implement changes and yet you insist that a country with a 233% more unemployment rate is better than the US. Look at the GDP growth between the two countries. Germany has glaical, if any, economic growth. 3 cars/100 people in the UK; 57 cars/100 people in the USA It's quite possible to achieve a good life without constantly working. Maybe in Germany a single-income family can still get by. Were we worse off when a woman could stay home and take care of kids? Your figure about 40% of the population in Germany not working full time may merely represent people making different choices. I've been to Germany, and I live in the USA, and I know where I see more people living in the streets. And it sure isn't Germany. And I think that's a fine measure of poverty. It's quite possible to achieve a good life without constantly working. Maybe in Germany a single-income family can still get by. Were we worse off when a woman could stay home and take care of kids? Your figure about 40% of the population in Germany not working full time may merely represent people making different choices. *Schroeders Economic Debacle: Over 5 Million Unemployed The high Euro means that if a European wants to buy an American product it costs 20% less than it a couple of years ago. How exactly is that bad for the Europeans? Because continental Western Europe's Big 3 (Germany, France, and Italy) all export more than they import, ergo their product costs more to buy on the world market. Germany - which is Europe's largest economy - exports $112 billion more than they import. *German Facts (Click on Economy or scroll down to it) Also, France is the most visited country in the world. Tourism is a large part of their economy. A high euro makes it more expensive to visit there. The few Europeans who have jobs? Are you actually asserting that most Europeans don't have jobs? That's absurd. Continental Western Europe's Big 3 all have unemployment rates over 10% (Germany is now at 12.6%) *More Euro Facts  German Workers:"For Us A One Way Trip On the TITANIC." "This, after all, is a country where, contrary to the picture of hard-working Germans, 40 per cent of the population is not in full-time work and people spend only 13 per cent of their lives in employment." Hope that helps explains things a bit better. The Europeans are doing just fine. We should be looking to them for advice on how to build an economy that actually benefits the working class, not just those who benefit from the labor of the working class. I'm going to be nice and just say "Good Grief!" Assume the average American worker enters the work force at 20 (college, you know), works until age 65, lives to the age of 75, that means that pesron spends 14.24% of his life working. Oh, fuck, I forgot to factor in vacations, holidays, time between jobs, etc. Probably lowers the number to, what, about 13%? "40% of the population is not in full-time work..." Yeah, kids don't work. Damn them do-gooder socialists and their child labor laws! "The US economy is 20 years ahead of that of the EU and it will take decades for Europe to catch up." 1978. 20 years to catch up (actually 26 years). But go on and claim that socialism is all good. Ok just to clear something else up, whenever you mention the economies of Europe you say the big three are Germany France and Italy, when of course they are not. The Big three are Germany France and Britain. As for comparing unemployment rates, you would need to investigate how these are calculated, would someone be able to say how US unemployment figures are calculated? For instance do you stop getting unemployment after 3 months even if you still don't have ajob and do you vanish from the figures? It's 6 months til you don't count anymore and that's only if you qualify for unemplyment in the first place. If you don't then you are never part of the figures. 'Only 10% of Americans have passports, and they say that as though its a bad thing' Jimmy Carr *American/Euro Culture Clash Education Many overseas students including executives from North America come to Europe for their management education. Many US business schools establish partnerships with European counterparts because of Europe's plurality, its many languages, its distinct business practices, ethics and a culture that values "the human element in the deal". Felix Mueller, the director of marketing, explains the attraction of a base in Europe. "We have all the advantages in research terms of a US business school but we need to combine it with a global view, which is why we're here. Many people complain that US schools are too US focused." *Comparing American and European business schools is academic The USA and Europe: Two, three or more economic cultures? Samuel Brittan: Gulbenkian Foundation Conference, Lisbon 21/10/03 Stylised Differences I have felt for a number of years that speakers on the economic front at this type of conference have had a difficult task. For if there is a growing divergence between the US and Europe it relates more to foreign policy and defence than to economics. There are of course some differences of economic philosophy, but they are often exaggerated. A characteristically forthright statement of the perceived differences has recently been given by the pro-free market Czech president Vaclav Klaus: "The USA has a much more liberal economy and a less heavy social system than Europe. The country is consistently more anti-statist, individualistic, laissez faire (and because of its dynamics actually more egalitarian) than other democracies. This is what produces its wealth and strength." He then goes on to praise American "life styles and cultural patterns, attitudes to work, courage and decisiveness. The currently fashionable European anti-Americanism and the caricaturing of American life and culture are frustrating." (CESinfo Forum, Munich, 2003) An American legal advocate, James Heckman, has gone further: "The world economy is more variable and less predictable today than it was 30 years ago when the modern European welfare state with its high level of taxation and regulation was established. This variability is associated with the entry of many countries into world trade, with the creation of new financial markets, with the explosion in technology and biotechnology." He cites the Italian case where applying national wage setting norms to the Mezzogiono are a cause of low employment in that region. By contrast he praises the reform of British unionism during the government of Margaret Thatcher when the locus of bargaining was shifted from the national and industry level to the firm level." (CESInfo, op.cit)  A remarkably similar picture was given, but from an opposite point of view, by a paper from the EU Commission presented at a conference I attended in 2000 at the EU University Institute in Florence. The authors examined several scenarios for the future; and the one they viewed with most horror was called "triumphant markets", which they identified with the American model and with materialism and consumerism. Such hostile attitudes are not confined to one part of the political spectrum. On the right they are seen in an extreme devotion to the nation state and a hostility to the European Union. On the left they often embody worship of an ill defined "community". My own impression is rather different. There are of course different attitudes to capitalism throughout the West, but they cut across continental divisions. If global capitalism is characterised by American values it is mainly because the US is certainly the largest and probably the most successful world economy. Some of the most strident attacks on capitalism, globalisation and international corporations which come across my desk come are the work of American authors. The differences are partly a matter of temperament. The English writer Dr Samuel Johnson once said that "a man is never more innocently employed than when making money." Even Lord Keynes, regarded as a hero by some of the critics of the American model, remarked that it was better that a rich man should tyrannise over his bank balance than over his fellow men. But there will always be those who instinctively recoil from the world of moneymaking, especially when the money is made by those whom they dislike.  What is perhaps different is that the anti-capitalist critique is given more house room in some European official circles, especially in "old Europe" (that is France, Germany and Belgium,) than it is in the USA. But even this needs to be qualified. New American administrations often come to power spouting protectionist rhetoric about the threat to American jobs from overseas competition, previously Japan and now China. President Clinton's favourite reading about the time he was first elected in 1992 consisted of attacks on unfair competition and a call for an interventionist US industrial policy; and after a less interventionist interregnum President George W.Bush is tending in the same direction.  The Rhenish Model It is helpful to recall a little piece of recent history. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989 it was no longer feasible to praise the virtues of state socialism. A different way had to be found of criticising capitalism. This took the form of identifying two forms of capitalism, the so-called Anglo-American or Anglo-Saxon one, to be avoided at all costs, and a "Rhenish" (Rhineland) model to be emulated by all progressives. The thesis was most elegantly enshrined in a book by Michel Albert entitled Capitalism against Capitalism (Whurr, 1991). His model refers to the countries around the Rhine valley and would have to be modified if applied to the rest of Europe. It is characterised by an extensive system of social protection leading to high social insurance contributions superimposed on the wage bill. The model is "institutional, collectivist and based on consensus." Employers and unions are regarded as "social partners" who work together to determine remuneration and working conditions. This is done formally and by law in Germany, but is emulated elsewhere. The aim of enterprises is not to maximise shareholder value, but to "reconcile the interests of clients, employees, shareholders and the social environment in general" - the so-called stakeholders. These procedures are helped by the modest role of the stock exchange and the importance of banks in financing enterprises. Reality, however, does not stand still. Since his book was published in 1991, the differences between the two forms have narrowed, as M. Albert has had the grace to emphasise himself. By 1997 he was asking whether the Rhenish model was suitable to a new age of technological innovation and increased international competition, which made job security more difficult to provide. He quoted the decision by the Daimler Benz group to alter its strategy so that it could be quoted on the New York Stock Exchange. He went on to question whether the internationalisation of capital in German and French enterprises was compatible with the notion of stakeholder value. He suggested that social benefits might have to be segmented rather than universal, by which he meant, I believe related more to workers' income and the particular circumstances of each enterprise. He feared that the transition would be difficult because the "social partners" were attached to the principles of equality (Max Planck Inst. Working Paper, January 1997). The move to Anglo-American modes has since gone still further. Continental European companies have been seeking stock exchange quotations, engaging in takeover bids and state industry has been privatised. Much of this was done quietly and without ideology to raise funds either for governments or for corporations. It has been said that the greatest privatisation in post-war Europe occurred while the socialist and critic of American capitalism, Francois Mitterand, was president of France or when Jospin was prime minister. The process has been caused "stealth capitalism" by the French writer, Alain Minc.  Unfortunately, although business practices have converged, the rhetoric of the political classes has not. While hostility to the USA has its roots in differences over global politics and perceived cultural differences, this generalised hostility to American ways slows down the pace of economic reform inside the European Union. There are of course still genuine differences in economic structure between the USA and Europe. The typical core EU country has a public spending ration of 50 per cent of GNP. The US ratio is more like 30 per cent. Where does the UK fit in? Where you would expect: fluctuating around a halfway position of about 40 per cent. But the USA itself is not nearly as uninhibitedly free market as such comparisons might suggest. Broad generalisations about the USA overlook the great differences between one state of the union and another. There is a burden of regulation which emanates very often from the individual state governments. Moreover some of the obstacles to business activity which are imposed in Europe by governments, are experienced in the US in the form of a litigation culture. It seems that almost any harm experienced by any person or group can be blamed on some corporation, and there is no shortage of well-paid lawyers to take up the cause. This American blame culture has been spreading to other countries, to the benefit of neither prosperity nor individual freedom.  The geographical interpretation of differences in institutions and ideas is often highly misleading. If we are embarking on a long historical quest, such as to explain why economic development started in certain parts of the world long before others, then indeed a lot of emphasis needs to be put on climate and therefore geography. But within the broad region known as the West, the most important modern differences now cut across national or continental boundaries. Indeed you can find as many ways of slicing the cake as you like. The supposed Anglo-American culture (which includes Australia and to some extent New Zealand) has been contrasted with the Rhineland model. But where then does Mediterranean Europe fit into the picture? You can regard Spanish and Portuguese cultures as a sub-section of the European variety; or you can talk of a Latin culture in which Spain, Portugal, Brazil and the Argentine are nearer to each other than to the central European land mass. But then where does Italy fit in? Or Scandinavia? Or the Slav world, part of which is soon to enter the European Union? Performance It is time to come back from these abstract international polemics to examine comparative performance. Some years after World War Two, "league tables" began to circulate comparing American and British growth rates to the six original members of the European Union - France, Germany, Italy, and the Benelux countries. The absurdity of this was to concentrate on rates of change rather than levels. The USA was starting the postwar period with such a high level of productivity and income per head that a long catch-up period was inevitable. (My own country, the UK, despite cultural similarities with the US, was a more genuine case of a laggard.)  This was a period when even hard-boiled American business executives studied French economic planning. The most that the sceptics could say that the German social market economy was doing just as well. Soon after it became the turn of Sweden to act as a role model, especially in left of centre circles. But then the comparison game began to change and it became fashionable to idolise the Japanese economy as well as some of the more authoritarian east Asian states. Such comparisons figured in the early Clinton campaigns, and it was not until well into the 1990's that American commentators began to realise that Japan had entered a decade or more of economic stagnation. As for Europe itself: according to the latest conventional wisdom Europe has been growing more slowly than the US as a result of structural "rigidities". The OECD has a rule of thumb for recent growth differentials: 3 per cent for the US, 2 per cent for Europe, and 1 per cent for Japan. Some of the differential is due to population growth, but not all of it. EU countries have themselves have signed up to reform declarations at one EU summit after another, starting with Lisbon in 2000. Doubt is cast on this conventional diagnosis by a recent paper, What's Wrong with Europe's Economy? by the former director of the Confederation of British Industries, Adair Turner in a paper given earlier this year (Adair-turner@ml.com). To start with, the facts are more complex than they are often made to appear. Turner puts under the microscope the difference between US and French GDP per capita, which put the US some 40 per cent ahead in 1999. Yet - and mark this fact - there was virtually no difference between output per hour in the two countries. The differences were due to two factors. American workers put in nearly 20 per cent more hours than French ones and the employment ratio per 1000 of the population was 15 per cent higher in the US. Turner rightly argues that if French people are happier with a shorter working week and a shorter working life than Americans - and are prepared to pay for it in lower take-home pay - then "no liberal economist should criticise them for that choice". Indeed it is American behaviour which is then more difficult to explain - "a society getting steadily richer, but totally focused on more income not more leisure".  I do not entirely accept the Turner thesis. As he concedes, shorter French working lifetimes may not be freely chosen. Some of the difference results from involuntary unemployment or involuntary early retirement, reflecting labour market distortions. The Scottish economist Adam Smith remarked: "There is an awful lot of ruin in a nation." Translated into modern English this means that a country can survive a lot of misconceived economic policies. The main reason why the continental model of early retirement, modest working hours and high social security payments cannot last is the impending demographic explosion in the number of elderly people. A shrinking labour force will have to pay heavy bills for unemployment and early retirement as well as for growing army of genuine pensioners. It is for this reason rather than any worship of GDP for its own sake that what US Defence Secretary Rumsfeld called "Old Europe" - Germany and France - would be well advised to take a new direction. Adair Turner, the sceptic from whom I was just quoting, does however score heavily when he belittles the so-called "Barcelona reform agenda". This consists of five main items: strengthening European transport networks; liberalising energy markets; further financial market liberalisation; promoting education and research; and reforming labour markets. The first four of these items are undoubtedly desirable. But their potential contribution either to promoting growth or improving employment prospects is slight. The all important item is of course labour market reform. There are political reasons why governments put this at the bottom of a list of underneath the four other items. An attack on union privileges or union-backed legislation is particularly sensitive, especially, but not only, for left of centre governments. Governments hope that they can get away with some freeing of labour markets if they bury the project under a great many worthy declarations on other subjects. Even when it comes to labour markets, we hear a lot of fashionable nonsense. An example is the importance attached to social security contributions on their own. If labour markets are reasonably flexible, "workers receive a lower wage rate than they would if payroll taxes were lower." (Turner) What are so obviously too high in some EU countries are total labour costs: wages plus payroll contributions. It would be just as valid to advocate cutting wages in some EU countries as cutting payroll contributions. The truly liberal answer would be to give the choice to the workers themselves.  Economic Disputes A good way of putting European and American differences into perspective is to look back at the failed WTO meeting in Cancun this September. In fact both areas exhibited a common narrow minded selfish defence of local interest groups. The US was unwilling - to take a blatant example - to curb cotton subsidies which strike very heavily at poor country producers. The European Union remain attached to its own farm subsidies. Japan behaved like a truly western country in its defence of its own heavily subsidised rice farmers.  The Group of 22 developing countries did not distinguish themselves either. They deliberately brought the talks to an end, despite much evidence that they had more to gain from lowering their trade barriers against each other even than from persuading the Western world to lower its barriers. In any case there was little material for those who wanted to differentiate between American and European economic philosophies. My own suggestion is that trade policy should be taken out of the hands of foreign ministries and trade negotiators - who regard every tariff cut or reduced barrier of any kind as a concession requiring compensation - to finance ministries, central banks and mainstream government economic advisers who can see that citizens in their own countries are among the biggest gainers from facing down the producer interest groups. Above all it would help if trade policy were no longer treated just as an arcane area for specialists. Instead the case for slashing barriers, unilaterally if necessary, should be treated as a part of the general liberalisation or free market agenda. Up to now this suggestion would have been rejected on the grounds that it would antagonise politicians of a more dirigiste bent, but after Cancun there is nothing to lose from a radically different approach. The Dollar Another cause of transatlantic tension has been what I call the crossover in macroeconomic policy between the USA and the European Union. Originally European countries were inclined to promote growth and full employment by monetary stimulation and budget deficits - a policy which rightly or wrongly was given the name "Keynesian" . American leaders long resisted such policies in favour of what was called the 'old time religion', meaning a devotion to balanced budgets and a cautious monetary policy. The latter was symbolised by the long term president of the Federal Reserve, William McChesney Martin, who clashed with President Kennedy. But around the time of the arrival of the Reagan administration in the early 1980s a crossover took place. US administrations, especially Republican ones, embarked on tax cuts to stimulate growth; and the Fed started to give the benefit of the doubt to policies of monetary expansion based on a highly optimistic view of productivity improvements. Originally in the Reagan era the tax cuts were justified on what were called supply side grounds - and which George Bush Snr once called "voodoo economics"; but his son George W Bush has embarked on unashamed demand stimulation and is impatient with a single quarter of growth below some imagined trend. By contrast, the EU has adopted the old time religion very firmly in the shape of the Growth and Stability Pact, even though some European countries look - perhaps fortunately - unable or unwilling to fulfil their fiscal undertakings.  An American economist and a British historian have combined to argue that recent increases in spending commitments by the Bush administration, together with long term tax cuts, will result in a budgetary shortfall in future years amounting to a present value of $45 trillion ($45,000 billion). This is way beyond anything that can be justified in the name of useful stimulation; and the authors raise the possibility of outright default on US debt - if not of legal obligations under social security and Medicare. Even the discussion of such possibilities could rock the bond market leading to higher longterm interest rates, and thus have the reverse effect of the stimulation intended by the administration. (Going Critical, Neil Ferguson and Laurence Jay Kotlikof, The National Interest, Fall 2003) Japan and Germany, the world's second and third largest world economies, face even bigger medium term fiscal crises. But neither of these countries aspires to be either a political super power or a dominant financial one. You do not have to look to these far horizons to see looming currency disputes between the two sides of the Atlantic. These go back to well before this crossover, indeed to the closing years of the Bretton Woods system in the 1960s. But they have been given a new edge by the ultra-Keynesian fervour of the Bush Administration. By far the most successful US policy towards its own currency has been to let it float freely - sometimes called "benign neglect". But there are occasions when the American Administration gets worked up either about the dollar being too high or too low. In the mid 1980s - around the time of the Plaza and Louvre agreements (1985-86) - the Reagan Administration expressed both worries in rapid succession. There is now a danger that the George W Bush Administration will follow in its footsteps and not be content to let the dollar find its own level, but try to push it down further in the interests of domestic exporters. As we have seen in the case of trade policy, the Bush administration is much more a pro-business government than it is a genuine supporter of competitive free markets. The immediate casus belli is the policy of China and other East Asian countries in trying to peg their own exchange rates to the dollar. The net result of their behaviour is to put more pressure on the dollar/euro exchange rate as the best way of securing an effective devaluation. If that happens my advice to European finance ministers and central bankers - which has no danger of being taken - is to lie back and enjoy the opportunity to improve their terms of trade and acquire dollar goods more cheaply.  Many people worry that if the Americans fail to get the Chinese to revalue that US drift to protection will go much further. But I am also afraid of an aggressive and sabre rattling reaction from the Europeans - I mean governments much more than the European Central Bank. Having failed to secure sustainable non-inflationary growth domestically they will feel challenged by a weakening of external demand. To give into these feelings would be mercantilist folly. If demand is growing too slowly for non-inflationary growth, then the remedy is a more expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. If it is not growing too slowly then there is nothing to be done apart from the boring but necessary work of improving European labour markets. Evaluation Let me finish by going back to the big picture, which is the debate on global capitalism. Anti-capitalist critics can of course make a good case against the corruptions of politicised capitalism. What they do not grasp is that international free trade and a competitive regime at home are the best defence against the political power of corporations. Such power can only exist if business interests can persuade governments to exclude competition, whether it is George W Bush trying to protect farmers or the steel industry or Gerhard Schroder, combining his pseudo-pacifist anti-Americanism with subsidies for German industry and labour. Moreover the most materialistic societies are those former Communist parts of Europe where economic performance is still so poor and poverty so great that it is natural for people to want to seize all they can. The two biggest delusions of the 20th century, which the 21st century has inherited, are first to assume that all human problems are the fault of, or can be remedied, by government, and secondly for governments themselves to seek an external scapegoat. This is the route to beggar-my-neighbour policies which as we saw in the 1930s did not do anyone any good. I am not a prophet and cannot say how likely this danger is but it is one we should seek to avert. Labels: Armageddon, Bible Prophecy, Bush Brotherhood of Death  Stumble It! Stumble It! |

Comments on "Comparing Europe To the USA"

post a comment